Einar D. G. Gunnlaugsson was born and raised in the barracks settlement on Skólavörðuholt. Although the barracks are long gone, the memories come alive through this exceptional storyteller. We got a glimpse into the past with him, hearing stories about life in the barracks and memorable pranks, not to mention the secret society on Holtið.

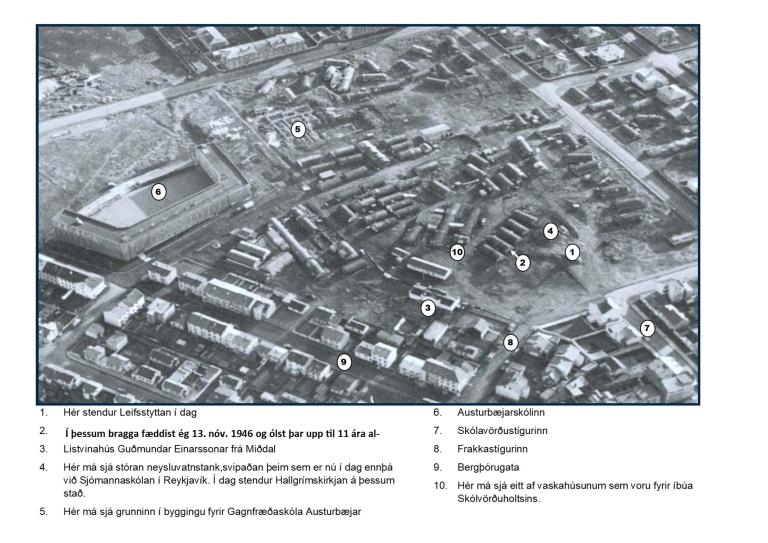

"This neighborhood was a paradise growing up, despite the poverty, and we got up to all sorts," says Einar, with undisguised nostalgia as he reminisces. Let's start at the beginning. "I was born on November 13, 1946, in Barracks Number 36 and grew up there. It was in a row of five barracks, behind the statue of Leifur Eiríksson. The people who lived there all came from outside Reykjavík, as newcomers were assigned to barracks. My father, Gunnlaugur Valdimarsson, was from Flatey in Breiðafjörður, but my mother, Oddbjörg Sonja Einarsdóttir, was born in the Faroe Islands and came to Iceland in 1944 to work at Kleppur Hospital. In some barracks, two families lived, each at one end, but we had an entire barracks to ourselves - my parents, my late brother Yngvinn Gunnlaugsson, and me. My father was often at sea, but my mother stayed with me in the barracks until I was four years old. Then she entered the workforce.“

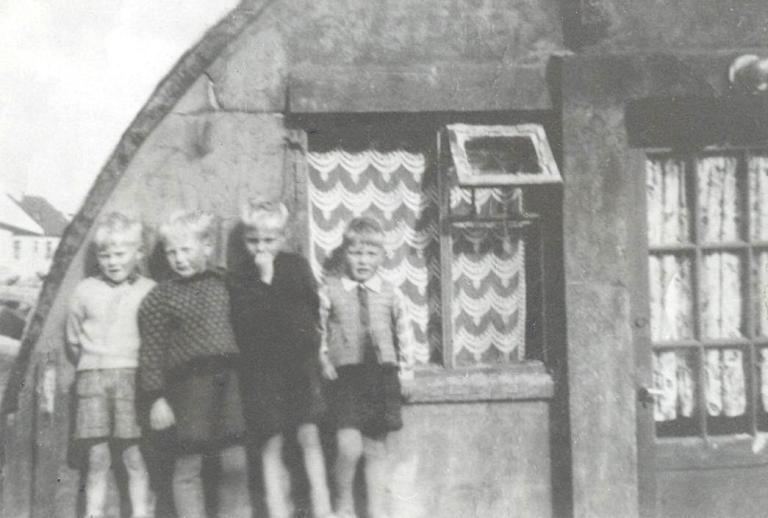

Photo from 1952. Here you can see the front of the barracks where Einar lived. Einar is on the far left, then you can see his friend Ásgeir Sigurðsson who lived in the only house in the barracks settlement, and finally the brothers Ólafur and Sigurður Theodórsson who lived in the same row of barracks as Einar.

"This neighborhood was a paradise growing up, despite the poverty"

Unwelcome barracks children

Einar says the children on Holtið were often restless, especially the boys. "Sometimes my playmates who lived 'in the houses' in nearby streets invited me home for snack time, but their mothers would sometimes tell me to go home and eat there instead. The reason was probably the smell of my clothes, as the barracks were not the best housing available. They were damp and musty, and most of us barracks children smelled like that. In these situations, there was nothing to do but leave the table and wait outside until my friends finished their snacks. Sometimes I also walked to the dairy shop at the corner of Kárastígur and Frakkastígur and begged for pastry ends. "They were usually thrown away, but some of the women in the shop saved the ends for us kids," says Einar, who remembers his childhood years fondly despite often being challenging. He explains that children in Holtið were often sent to foster care, and he briefly stayed at Korpúlfsstaðir and Minni Ólafsvellir. "When my mother went to work, I was left with her Faroese friend, who was the kitchen manager at Vífilsstaðir. I ate with the staff there, but being curious, I wandered around everywhere. I often visited people lying on sun loungers behind the long wall connected to the hospital, but chaos ensued when my visits to tuberculosis patients were discovered. I don't remember being examined by doctors when this interaction was discovered."

Einar has researched old photographs extensively. Sigurhans Vignir/Reykjavík Museum of Photography.

Under the wing of Guðmundur from Miðdalur and family

Daily life in Holtið was colorful. Among other places, there was Guðmundur Einarsson from Miðdalur's Art Friends House (I. Listvinahús), which Einar started visiting regularly around age 8. "My dear Einar, since you're always hanging around here, you might as well do some work," said Einar Guðmundsson, the potter and son of Guðmundur from Miðdalur, to Einar one day. He showed him tasks where ravens, ptarmigans, and other well-known clay objects were being produced. "I felt honored and found the work enjoyable. Sometimes I also went with Bangi, as Einar was called, to get clay from a quarry at Norðlingaholt, and occasionally I got to make small clay objects by hand. I especially remember an ashtray I gave my mother. Bangi painted and fired it for me, and I thought it was the most beautiful ashtray ever made," says Einar. "My father was often away, and my mother worked shifts at the Axminster carpet factory, so I often went hungry during the day. The father and son noticed this, and Bangi often called me to deliver a package to his aunt Lidía on Skólavörðustígur, where she and Guðmundur lived. When I arrived at Lidía's, she always said to me: "You're lucky, my dear Einar. I was just about to have some coffee. Won't you come in and have a glass of milk and a slice of bread with me?" In my innocence, I thought I was lucky and accepted the offer, only to find out much later that all those packages were empty! Bangi simply called Lidía when he saw my condition and asked her to give me something to eat. They were exceptionally kind to me.“

Here you can see Einar in his childhood neighborhood, around six years old.

Youngest customer of the liquor stores

Einar had considerable interactions with Guðmundur from Miðdalur's family. When Erró, Guðmundur's other son, was tiling the entrance of the Trade School, Einar spent a lot of time with him. "In the end, he got a chair for me, and we chatted about where the tiles should go," Einar says, smiling at the memory. "Once, Guðmundur called for me, and I went to him where he had a workspace for creating prototypes of the statues produced in the Art Friends House. He asked me to go to the 'State' (liquor store) and give the clerk a brown paper bag he had written on: "Dear recipient. Please give the boy 1 bottle of VAT 69. I'll come and pay later. Guðmundur from Miðdalur“. I was handed the bottle, a boy not quite nine years old, without comment. Then the clerk folded Guðmundur's bag and put it in the cash register. I'm probably the youngest customer of ÁTVR (State Alcohol and Tobacco Company of Iceland) ever," he adds, laughing heartily.

"When we came home to Holtið, our parents greeted us with clenched fists. We didn't know what hit us."

Unpopular balloon sellers

At six years old, Einar started school at Landakotsskóli, where his mother had gotten a job at the Ægir laundromat on Bárugata. The walk to and from school could be long for little feet, but it was fun to stop at Tjörnin to play on the way home and sometimes lose track of time there late into the day. Einar doesn't have good memories from Landakotsskóli, though, and at eight years old, he moved to Miðbæjarskóli, which he liked better.

But the story turns back to life in Holtið, where various activities took place. "When I was about eight years old, the Ella Ling shop was run on Frakkastígur, selling Freyja sticks and chocolate rolls. Once, we were wondering how to get money for some treats. My friend said his mom had lots of balloons at home. We got them and sold the balloons to all the kids for five aurar each. We took the money to the corner store, but when we returned to Holtið, our parents greeted us with clenched fists. We were confused until we learned my friend had stolen a pack of condoms from his mom. "Everything went crazy and we got a lecture, but we got the chocolate cigars," he says, laughing heartily.

Einar was born in 1946 in the barracks to the left of Leifur Eiríksson's statue and lived there until 1957. Guðbjörg María Benediktsdóttir/Reykjavík Museum of Photography.

Intimidating admission requirements

The boys in the barracks settlement had a secret club for members aged 7-12. "The entry requirement was to climb up the marble ship on Leifur the Lucky's statue and reach the top to place your palm on Leifur's helmet. I was 8 when I attempted this challenge. Luckily, I succeeded despite the slippery marble from rain and wearing old rubber shoes. "Fortunately, none of the boys got hurt during this dangerous climb. I still get chills when I see the statue," Einar recalls, shaking his head. "Once in the secret club, you could join in stealing turnips from Vatnsmýri and pigeons from boys living in 'houses' around Holtið. We could also attend candlelit meetings in the garden behind Guðmundur frá Miðdal's Art Friends House."

Einar still gets chills seeing Leifur Eiríksson's statue, remembering when he climbed it at age 8 to join the secret club in Holtið.

Washtubs...or boats?

The list of the club members' antics seems endless. "In Holtið, there was a huge water tank, very tall and covered with turf on the outside. On top of it was a loose steel plate, and we often toyed with the idea of removing it and swimming inside, but luckily we never did," says Einar. However, various ideas were carried out, much to the varying delight of the adults. "In Holtið, there was a shared laundromat for the women, where they had several large wooden tubs for rinsing white clothes. Nearby was a very deep hollow with a drain at the bottom. Once, when it rained heavily, we boys blocked the drain. When a pond formed, we emptied the bales, rolled them down, and used them as boats. Of course, everyone went crazy! We tried to stay in the middle of the puddle as long as we could, but eventually, the men waded in and got us. "This wasn't popular," Einar adds, grinning at these colorful memories.

The city's appearance has changed dramatically during Einar's lifetime. When he lived in Holtið, Hallgrímskirkja was just a chapel. "You only went there to get Bible pictures. But it was remarkable that when you entered the chapel, you always bowed when passing the Christ statue, involuntarily. I was baptized there at two years old," he says, adding that his name comes with a sad story. "My mother's best friend was once going to the milk shop on the corner of Kárastígur and Frakkastígur. She had her son in a stroller, but the brake failed, and the stroller rolled under one of those Reykjavík trucks often used for rock transport and other things. The boy died, and before I was baptized, his mother asked my mother to give me his name. So it happened, and my D. G. stands for Davíð Georg."

"When a pond formed, we emptied the bales, rolled them down, and used them as boats. Of course, everyone went crazy!"

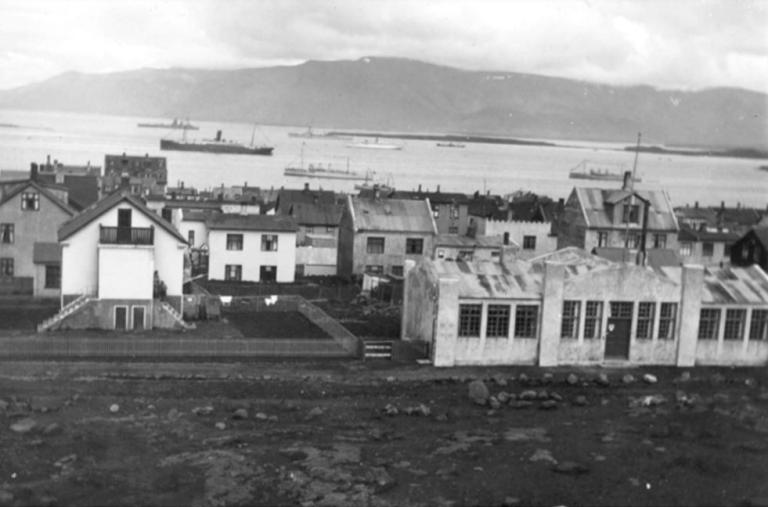

Guðmundur from Miðdal's Art Friends House on the right side of the image. Ships in Faxaflói in the background, including warships and merchant ships, possibly Danish patrol vessels. Photo: Karl Christian Nielsen/Reykjavík Museum of Photography.

A couple with various talents

Einar recalls countless stories, and only a fraction are told here. As an adult, he became a technical draftsman after leaving his baker apprenticeship at Sveinsbakarí due to a wheat germ allergy. He lived in several places in Reykjavík and Hafnarfjörður, spent about ten years in Höfn as a correspondent for Morgunblaðið, and now lives with his wife, Þóra Margrét Sigurðardóttir, in Hraunborgir in Grímsnes. They spend most of the year there but seek the sun in Tenerife during the darkest months. They've retired from traditional day jobs but are true jacks-of-all-trades. They sell homemade bread and jams, sauces and pickles, knitted goods, and images Einar paints for postcards. They also rent a guesthouse to tourists. Sales occur online and at the market in the Service Center in Hraunborgar during summer. In autumn, a different season begins as they bake and sell about 6,000 Sarah cookies for Christmas. Life is never dull for this married couple, who have three children, six grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren.

"The changes in the city since I grew up are incredible, but I think modern Reykjavík is fantastic!"

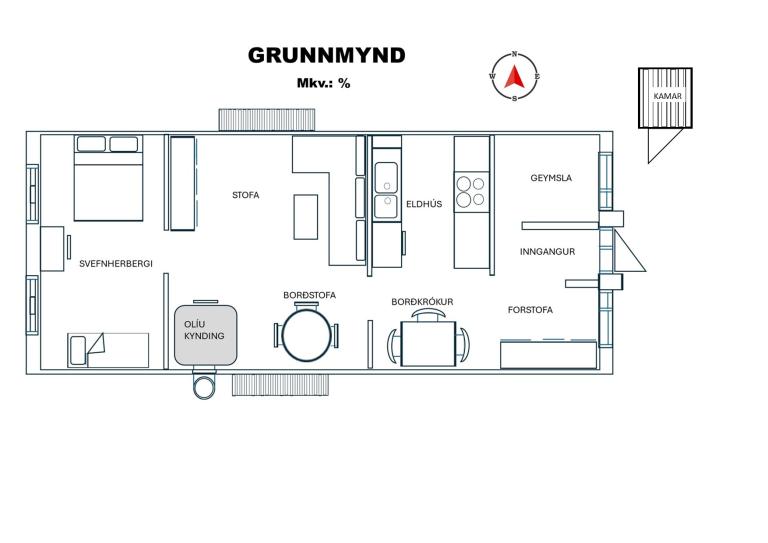

Here you can see a floor plan of the barracks where Einar lived, created by the technical draftsman himself.

Nostalgia at Skólavörðuholt

Although Einar has moved to the countryside, he often visits his old neighborhood. "When I come to Skólavörðuholt, I'm overwhelmed with nostalgia. The changes in the city since I grew up are incredible, but I think modern Reykjavík is fantastic!" he emphasizes. "My only concern is that the densification might become a bit too much, and I think it's unfortunate that access to Laugavegur was limited. Still, my favorite place in the city is the entire city center, and I find the restaurant scene wonderful," he adds decisively.

It's easy to lose track of time listening to Einar's entertaining stories. We bid farewell to this fantastic storyteller and thank him warmly for allowing us to glimpse into Reykjavík's past with him.

An aerial photo shows how the barracks settlement stood out among the houses. Sigurhans Vignir/Reykjavík Museum of Photography.