Serious abuse cases referred to police by Child Protection rarely lead to prosecution

Few cases referred to police by Reykjavík Child Protection Services, where serious child abuse is suspected, result in prosecution. This is shown in the master's research of Elísabet Gunnarsdóttir, an experienced social worker and division head at Reykjavík Child Protection Services.

Elísabet has worked at Reykjavík Child Protection Services for 18 years. She began as an intern in the foster care team, where she worked until 2020 when she was appointed division head of a new assessment and treatment team focusing on children of foreign origin and domestic violence cases. Elísabet's insight and experience led her to analyze cases from Reykjavík Child Protection Services' records to examine the outcomes of cases where serious child abuse was suspected and referred to police investigation. The research was her final project for her master's degree in social work at the University of Iceland.

Referring cases to police investigation not a light decision

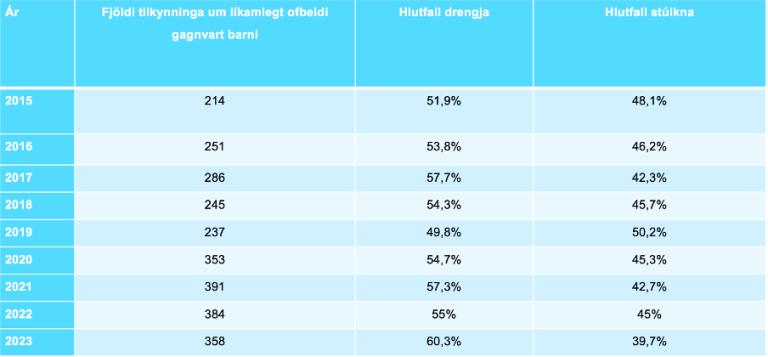

The study examined all cases where children were suspected of suffering serious physical abuse from their parents between 2015 and 2023. During this period, reports to Child Protection Services about child abuse increased significantly. They numbered 214 in 2015 but rose to 358 in 2023.

Number of reports received by Reykjavík Child Protection Services during 2015-2023:

Elísabet examined a total of 113 cases. This shows that only a small portion of cases reported to Child Protection Services are ultimately referred to police. The decision to refer cases to police is based on laws, regulations and specific procedures issued by the National Agency for Children and Families. Despite this, the decision also depends on the judgment of Child Protection staff, which Elísabet says can be complicated. "We make all decisions as a team; no one makes decisions alone. But it can often be difficult for us to assess these cases, because referring a case to police can negatively impact our cooperation with a parent, while we're simultaneously working on a treatment plan and proposing specific interventions. We always need to assess whether it's in the child's best interest for their case to go that route, or whether it's more beneficial to use the parents' willingness to cooperate to improve the child's living conditions."

"We make all decisions as a team; no one makes decisions alone."

Elísabet's complete research can be viewed on Skemman (the Icelandic academic repository).

Most children are of foreign origin

In the majority of cases referred to police, or 67%, the children are of foreign origin. Elísabet believes this has two main explanations. "Research shows that being a refugee or immigrant is a risk factor for abuse. This underscores how important it is to support people moving to this country, often from difficult circumstances, as they are frequently under significant stress. Cultural differences and varying attitudes toward child discipline and violence also play a role. Culture certainly doesn't justify child abuse, but we must take this into account. Our role is to guide people, point them in the right direction, and show them where they can get help with their parenting responsibilities. Sometimes we need to inform people that in this country, it's illegal to use physical punishment on children for disciplinary purposes. We meet people who don't know that."

Elísabet points out that most cases at Reykjavík Child Protection Services are handled in good cooperation with parents, contrary to what many believe. "When we make recommendations, the problem has often become so significant that in most cases, parents agree with us. We are advocates for the children with their rights and interests as our top priority, and many parents understand that."

Hopes child abuse cases receive higher priority

Elísabet's research findings show that charges are filed in very few cases, only 19% of them. Ten parents out of 89 suspects were convicted, while charges were filed against 11 parents. "This low percentage indicates to some extent that it's better for us to try everything we can before referring cases to the police," Elísabet says.

Elísabet says she's found significant interest from the police in the research findings. She worked closely with the police while conducting the research, as information about the outcomes of all cases wasn't available in Child Protection Services' records.

"I hope this research will help ensure more cases are taken seriously by the police after our assessment at Child Protection Services. There's every reason to do so, as these are the most serious cases that come across our desk."